Geology, landform, water systems and climate

The High Weald countryside gets its ridges, valleys and rolling landscape from the underlying bands of sandstone and clay.

The harder sandstone forms the high land and ridges, which generally run east-west across the High Weald.

The lower land between the sandstone ridges is the result of the softer clays having been more easily eroded.

The action of the elements over time has unevenly eroded these sandstones and clays to leave the steeply ridged and folded countryside that survives today.

Geology, landform and water systems are a key component of the High Weald’s natural beauty. Policy objectives for these landscape features are set out in the High Weald AONB Management Plan, pages 24-29.

Layers of sediment

The sandstones and clays of the High Weald were originally laid down as sandy and muddy sediments.

Starting around 140 million years ago (when dinosaurs still roamed) these sediments formed at the bottom of shallow lakes, or were carried by rivers and deposited on floodplains.

Around 100 million years ago, sea levels rose and the remains of billions of tiny sea creatures then formed another layer of sediment above the sands and muds. Over time, this became chalk.

Uplift and erosion

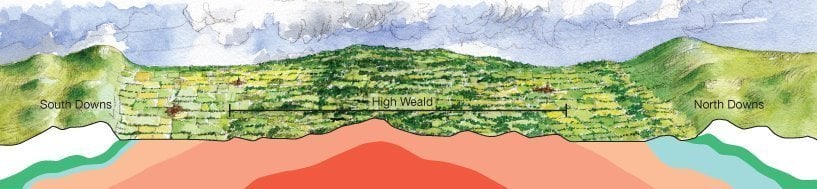

Around 30 million years ago, massive earth movements began to push all the compacted layers of sediment up, creating a giant, chalk-covered dome.

Over time, water eroded most of the chalk away, revealing the older sandstones and clays beneath – the High and Low Weald. The chalk at the edges of the dome has remained – forming the North and South Downs.

Rock outcrops and gills

The hardest areas of sandstone now form the distinctive sandrock outcrops of the High Weald. In addition, fast-flowing streams have carved out characteristic, steep-sided ravines called gills in the steep sides of the sandstone ridges.

The porous, moisture-holding sandrock and sheltered, damp gills provide ideal living conditions for ferns, mosses, liverworts and lichens. Many of these species are more characteristic of the mild and humid oceanic climate of Wales and Cornwall than that of the South East.

Most famous is the tiny, and extremely rare, Tunbridge Filmy-fern.